|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Congo (Kinshasa): Ebola Response Shows Lessons Learned

AfricaFocus Bulletin

June 20, 2018 (180620)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

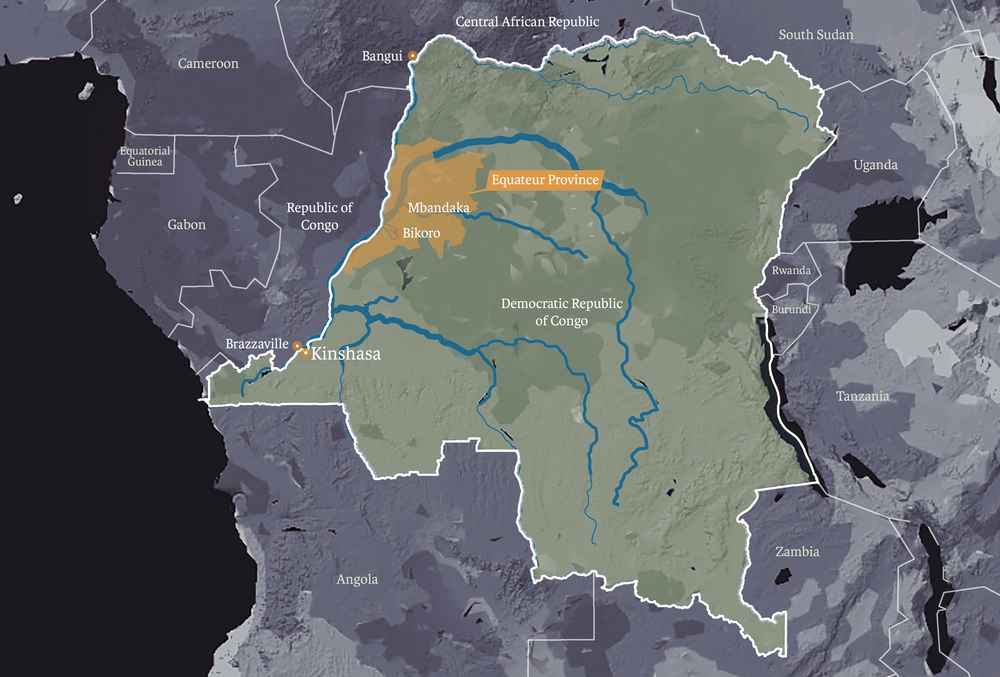

The Democratic Republic of Congo has extensive experience in successfully containing

Ebola outbreaks (the one which was reported in May is the ninth since the first in

1976). But this one, with cases in Mbandaka, a river-port city of over one million

people on the country's western border, raised the nightmare scenario of spreading to

other river-port cities such as the capital Kinshasa (over 11 million people), as well

as Brazzaville in the Republic of the Congo, and Bangui in the Central African

Republic. But, although victory is not assured, so far the response by national and

international health agencies has been a model of applying lessons learned.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains three articles, one

providing basic background, another by a Ugandan Ebola expert leading

"ring vaccination" efforts making use of a new vaccine, and the other

by a Kinshasa-based journalist with interviews highlighting the role of community involvement.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on the Democratic Republic of Congo, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/country/congokin.php

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on Ebola, see particularly

http://www.africafocus.org/docs15/eb1505.php and

http://www.africafocus.org/docs15/who1501.php

ReliefWeb Current Updates

https://reliefweb.int/disaster/ep-2018-000049-cod

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Ebola outbreak in Congo: What you need to know

Kinshasa, IRIN News, 21 May 2018

by Issa Sikiti da Silva

An award-winning Kinshasa-based journalist

http://www.irinnews.org – direct URL: http://tinyurl.com/ybksfydr

The Democratic Republic of Congo has begun to administer an experimental vaccine to

halt the spread of the Ebola virus in Mbandaka, a major transport hub that is home to

more than one million people and connected by river to several other large cities.

The illness, a particularly deadly form of haemorrhagic fever, killed more than

11,000 people in an epidemic that swept through West Africa in 2014-16. Here’s our

briefing:

When did the new outbreak begin?

This isn’t entirely clear. Cases of haemorrhagic fever had been reported in the same

region as early as December 2017, with some deaths reported in January. But this

possible first wave of cases was never confirmed as Ebola. Local health authorities

reportedly did not immediately share news of the cases, which they received on 1

March, with the national health ministry. Ebola can’t be ruled out as no lab tests

were ever done.

What we do know for sure is that on 8 May, DRC’s Ministry of Health notified the

World Health Organization, or WHO, of 32 possible cases (which had led to 18 deaths)

recorded since early April in northwestern Equateur Province. It said two of these

had been confirmed by laboratory tests to be Ebola, 18 were categorised as

“probable”, and the remaining 12 as “suspected”. Three of the 32 cases were detected

in healthcare workers. On the same day, the government of DRC declared a “public

health emergency with international impact”.

A nurse prepares the Ebola vaccine in Bikoro in the DRC. MSF/Louise Annaud]

How many people are now infected?

As of 20 May, the Ministry of Health had recorded 46 cases of haemorrhagic fever,

including 26 deaths. Of these, 21 are confirmed to be Ebola, 21 are “probable”, and

four are “suspected.”

Four of the 21 confirmed cases were recorded in Mbandaka, which has heightened

concern about the spread of the disease. The Ebola virus spreads quickly in urban

areas, and Mbandaka is a key transit link to three capitals: Kinshasa, Brazzaville,

and Bangui. The city is 280 kilometres from the area where the first cases were

confirmed.

Has Congo had other recent outbreaks?

This is DRC’s ninth Ebola outbreak since 1976. The others were centred in rural areas

and contained before they reached an urban environment like Mbandaka. The current

outbreak is the fourth in Equateur Province – following others in 1976, 1977, and

2014.

Will the virus spread to other densely populated areas?

No one knows for sure, but that’s the fear. Four confirmed cases in Mbandaka lend

some weight to it.

On 21 May, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus tweeted: “It’s concerning

that we now have cases of #Ebola in an urban centre in #DRC, but we are much better

placed to deal with this outbreak than we were in 2014. I’m pleased to say that

vaccination is starting as we speak."

Last week, Tedros refrained from declaring the outbreak a “public health emergency of

international concern”.

What’s being done to monitor its spread?

DRC Health Minister Oly Ilunga said last week that monitoring travellers for signs of

the illness would be stepped up along all air, sea, and overland routes in and out of

Mbandaka. In addition, wider Equateur Province (including villages up and downstream

from Mbandaka on the Congo River) was to be put under close watch by healthcare

workers and officials.

River routes are popular in DRC because only two percent of the country’s 152,000-

kilometre road network is paved. Mbandaka port on the Congo river bustles with

vessels ranging from small pirogues to larger ships that travel with passengers to

Kinshasa. DRC’s capital is about 600 kilometres to the south and home to some 12

million people. Several other port towns with sizeable populations dot the route.

Brazzaville, the capital of the Republic of Congo, is across the river from Kinshasa.

Mbandaka is also connected, via the Oubangui River, to Bangui, the capital of the

Central African Republic.

Effectively monitoring all of DRC’s waterways is impossible. Kinshasa alone has 20

different makeshift ports. Vessels plying the Congo River and its many tributaries

are often overloaded or in poor repair, and their captains don’t welcome enquiries

from officials. Many, also, dock at night.

Additionally, the government workers who carry out such monitoring often receive

their salaries late and are poorly trained and/or part of understaffed teams. Morale

is often low, which means the zeal with which they do their job may be, too.

Who’s doing what to tackle the outbreak?

Both the Congolese government and international organisations are on it.

The Ministry of Health launched a ring vaccination campaign – the first time, outside

of a clinical trial, that a vaccine has been deployed to stem an Ebola outbreak – on

21 May. It has also sent rapid response teams to Equateur Province to investigate

reports of cases and deaths.

The WHO has released $1 million from its contingency fund for emergencies and

provided technical and operations support, activating a multi-partner, multi-agency

Emergency Operations Centre to coordinate the response. It has also shared risk

communication materials in French and Lingala (the Bantu language spoken in the

region) with local DRC offices.

Médecins Sans Frontières is setting up an Ebola treatment centre in Bikoro health

zone where the first cases were discovered.

UNICEF is working with government officials on strategies for communication and

ensuring safe water and sanitation practices as well as health and psychosocial care.

It has also distributed supplies to the affected areas, including 4,585 kg of soap,

tarpaulins, buckets, and chlorine to support sanitation and hygiene. A total of 80

tonnes of UNICEF aid is also being transported from Sierra Leone to the DRC.

A Red Cross team of experts in Equateur Province is providing training and support to

local volunteers. It has brought supplies such as stretchers, chlorine disinfectant,

burial kits, informational posters, and other items to support local communities and

health centres. More than 110 Red Cross volunteers in Bikoro and Mbandaka are

alerting residents of the outbreak and disinfecting houses where people with

suspected cases reside. They also provide safe burials if needed. The effective

management of victims’ bodies is crucial to an effective Ebola response.

Local teams from the Ikoko-Impenge health centre and Bikoro General Reference

Hospital are monitoring patients for signs of the illness.

Wellcome Trust, a biomedical research charity based in London, is providing two

million pounds (2.68 million dollars) for research to support the operational

response.

How does ring vaccination work?

Ring vaccination differs from mass vaccination in that it targets concentric circles,

or rings, of people vulnerable to infection. The process starts with health workers

and those who may have had contact with infected people, as well as contacts of

contacts. First in line are 600 people, including medical staff.

Four thousand doses are already in Congo and more are coming.

The vaccine being used in Congo, rVSV?G-ZEBOV-GP, is termed experimental because it

hasn’t been licensed for general distribution. It is being deployed on a voluntary

basis under a protocol called the Expanded Access Framework. Informed consent is

required from those receiving the vaccine, which means translators and discussions

that last about 45 minutes.

A network of “social mobilisers” has begun meeting with leaders of local communities

to explain the vaccination process and other issues related to the outbreak.

According to the WHO, “the vaccine works by replacing a gene from a harmless virus

known as vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) with a gene encoding an Ebola virus surface

protein. The vaccine does not contain any live Ebola virus.”

The vaccine, which has been judged safe for human use, is delivered via an injection

into the arm. People are checked three days after they receive it, and again after 14

days. The vaccine only provides protection before infection has occurred – anyone

infected with the Ebola virus before being vaccinated will not be protected.

Possible side effects of the vaccine include mild fever or cold like symptoms and, in

very rare cases, allergic reactions to the injection.

Experts from Guinea, one of the West African countries badly affected by the 2014-16

epidemic that killed more than 11,000 people, are in Mbandaka helping with the

vaccinations. Some 7,500 adults in Guinea received the vaccine in 2015, when it was

shown to be “highly protective”, according to WHO spokesman Tarik Jašarevic.

Logistical challenges in delivering the vaccine include DRC’s poor infrastructure and

the requirement that it be stored at between -60 and -80 degrees Celsius.

How do humans become infected with the Ebola virus?

Fruit bats are thought to be the natural host of the virus. Bats can infect other

animals common in the forests of Congo, such as monkeys, antelopes, shrews,

porcupines, and chimpanzees. Humans become infected when they come into contact with

the organs or bodily fluids of these animals, which are widely eaten as bushmeat in

northwest DRC.

"Bat and monkey meats are delicious meals, as prescribed by our forefathers," Justin

Efongo, a Kinshasa resident who was born in Bikoro, said. “It will be difficult to

convince these people to give up on what is their favourite meal. The forest is huge,

and God gave us all the food that is in there. Ebola is a curse, not a real disease.”

http://theconversation.com – direct URL: http://tinyurl.com/y9sqexu8

Challenges of administering an Ebola vaccine in remote areas of the DRC

June 14, 2018

Yap Boum

Professor in the faculty of Medicine, Mbarara University of Science and Technology,

Uganda (http://must.ac.ug/)

No one said tracking the movements of a patient, suspected to be a carrier of the

deadly Ebola virus, through the dense forests of the eastern region of the Democratic

Republic of Congo (DRC) was going to be easy.

With no discernible roads, only dense bush, we were forced to travel on three

motorbikes to get to our destination, riding through areas where no car could reach.

There were six of us: a research investigator, a medical doctor, an officer

monitoring water, sanitation, safety and security and the three motorbike drivers.

After almost three hours we finally found our destination: a village in the middle of

the forest. This was Bokongo.

It took our epidemiologist several days to find this remote village. He was tracing

the travels and contacts of just one patient suspected of having Ebola. Just before

the epidemiologist broke his leg, he identified some contacts and first line workers

that needed to receive the Ebola vaccine.

After arriving in Bokongo we managed to vaccinate 13 first line workers. But ours was

not the only operation.

As health authorities in the Democratic Republic of Congo continue to try and contain

the Ebola outbreak in the north eastern region of the country, there are several

teams vaccinating targeted populations in Bikoro, Ikoko-Impenge, Itipo, Mbandaka and

Iboko.

The country’s health ministry has stepped in to coordinate the response to the

outbreak. And the World Health Organization, Médecins Sans Frontières, Epicentre and

others organisations have sent teams of specialists to assist.

As a result more than 1500 people have been vaccinated so far. But already 27 people

have died since the outbreak was declared on May 8, 2018. Ours is a race against time

– making sure we get to everyone who could possibly be infected before the deadly

virus does.

Part of the team

It’s not the first time that I have been part of an Ebola response. As the African

representative of Epicentre – the research arm of Médecins Sans Frontières – I have

been involved in Ebola response since 2012 during the Kibaale outbreak in Uganda.

At the time I led Epicentre’s Mbarara Research Centre. Then I coordinated the field

and laboratory part of the clinical trial assessing vaccine’s efficacy, safety and

performance on first line workers in Guinea during the Ebola outbreak in 2014 to

2015.

The vaccine was also considered during the 2017 outbreak in Likati in the DRC. But

the Likati Ebola outbreak ended with a limited number of cases and the vaccine didn’t

have to be used.

With the current outbreak in the DRC I came to the capital city, Kinshasa, two days

after the outbreak was officially declared to assess the situation and see whether or

not the vaccine could be part of the response.

The increasing number of cases and the fact that the outbreak had reached an urban

area (Mbandaka) meant it was clear that the vaccine would be an additional tool for

the response.

Testing a new vaccine

The vaccination is administered using a “ring” approach. This involves identifying

newly diagnosed and laboratory confirmed Ebola patients. Epidemiologists first need

to locate the people they have been in contact with. And then the patients and their

contacts -— often family members, neighbours, colleagues and friends -— constitute

the ring who all get vaccinated. First line workers from the health area where an

Ebola case has been detected also qualify to receive the vaccine.

This method of investigating contacts is one of the biggest challenges when

administering the vaccine. Tracing and following people to the middle of the forest

presents a massive logistic challenge – which means that it can take days to find

people who need the vaccine most.

The Ebola vaccine is known as a recombinant vaccine. This means that the glycoprotein

of the Ebola virus has replaced the glycoprotein of another virus. The glycoprotein

is important because it builds antibodies against a virus. Ebola’s glycoprotein was

added to the vesicular stomatitis virus, which is not harmful to humans. People are

given the vaccination so that they can immediately build antibodies against the Ebola

virus.

The vaccine was discovered by a small Canadian company and later bought by the big

pharmaceutical company Merck. The vaccine is still not licensed but it’s known as

VP920.

Several studies across the US, Switzerland, Gabon and Kenya have assessed the safety

of the vaccine which targets the Zaire strain of the Ebola virus.

Its safety, efficacy and immunogenicity was also assessed during the Ebola outbreak

in West Africa in 2014; the results have shown great safety efficacy and

effectiveness. The vaccine is still in the process of being registered – but this is

a really long procedure.

The logistics

One of my primary responsibilities has been ensuring that the teams that administer

the vaccine have everything we need in this process. I’ve also coordinated our

activities with health officials, the WHO and the country’s extended programme for

immunisation so that they understand how the vaccine is administered.

To launch the vaccine in this outbreak we’ve had to train the locally recruited staff

about Ebola, the study protocol as well as good clinical practices. This includes

ensuring everyone who gets the vaccine consents to it, understands the study and

possible side effects.

This has been difficult because we only have a limited time to teach people about the

dangers of the virus as well as the importance of the protocols when they are out in

the field.

While the WHO team started administering the vaccine in Mbandaka, the MSF/Epicentre

team went in Bikoro where all the confirmed cases from Itipo – the epicentre of the

outbreak – were referred.

Since then vaccination drives have not stopped. Each time we enter a village we’re

greeted by one of the most frightening moments knowing that we’re surrounded by

people who have been in contact with the deadly virus but may not have been traced.

But then we look into the eyes of the people full of hope and we’re reminded about

why we do what we do: to make a difference by reaching the unreachable.

Songs, radio shows, and door-to-door visits: how community awareness is helping

defeat Ebola in Congo

Containing the outbreak isn’t simply down to the vaccine

Mbandaka/The Democratic Republic of Congo, 7 June 2018

Issa Sikiti da Silva, An award-winning Kinshasa-based journalist

http://irinnews.org – direct URL: http://tinyurl.com/y9r9xdoy

Relatives ride in on motorbikes, bust three patients out of an Ebola treatment

centre, and take them to a church to be prayed over by 50 people. Later, one dies at

home, another in hospital, while the third lives but could have infected an untold

number of people.

It sounds like a scene from a Hollywood disaster movie, but it took place less than

three weeks ago in Mbandaka, a city of 1.2 million people in the Democratic Republic

of Congo. A huge effort is now underway here to raise awareness about the virus and

prevent its spread.

The government and international NGOs are leading the charge, but some of the most

effective work is done by the local community and Church leaders. In the Roman

Catholic archdiocese of Mbandaka-Bikoro, for instance, sacraments such as baptisms

and anointing ceremonies have been suspended to avert the risk of transmitting Ebola.

“Ebola is real,” stressed community leader Gabriel Selemani at an impromptu gathering

near a marketplace. “Don’t play games with it, and don’t listen to rumours and lies

being spread around that it is a fairy-tale, an international conspiracy, or as a

result of witchcraft.”

In local schools in Mbandaka, teachers hammer home the message too, leading children

through a special “Ebola, Go away!” song and making hand-washing and temperaturetaking

mandatory before class.

Talking to people on the city’s streets, it is evident that many take the dangers

posed by the outbreak extremely seriously. But others disregard the risks, while some

are in denial about the outbreak or say they believe news of it has been planted as

some kind of Western plot.

...

Contained? Perhaps, for now

News of Congo’s latest Ebola outbreak (this is its ninth since the first-ever case

was discovered near the country’s Ebola River in 1976) emerged in early May in the

northwestern province of Equateur.

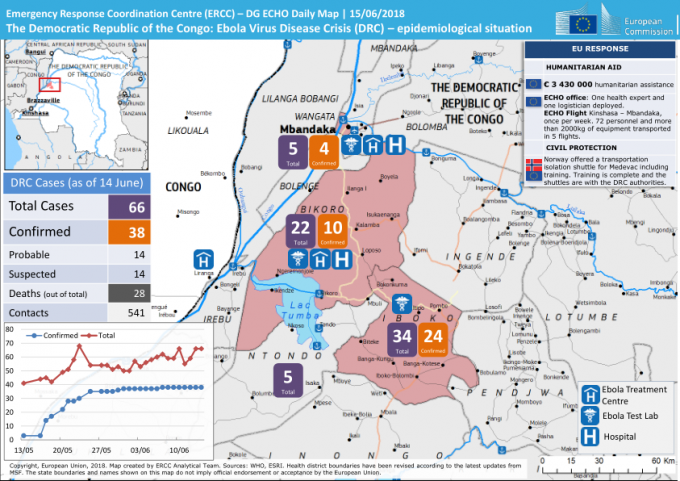

As of Thursday (May 31), 37 Ebola cases had been confirmed, all in Equateur,

including 25 deaths, according to the World Health Organisation.

Infographic below shows the situation as of June 14

...

The greatest fear remains: that an infected person could carry the disease to a major

urban centre, like the capital, Kinshasa, or Bangui, the capital of neighbouring

Central African Republic – both reachable via the largely unmonitored Congo River.

This time around, a new weapon has been deployed in the fight against Ebola – a

vaccine, administered to anyone who comes into contact with a confirmed case. Tested

towards the end of the West Africa epidemic that claimed more than 11,000 lives from

2013-16, this is the first time a vaccine has been part of a concerted effort to

contain an Ebola outbreak.

For the so-called ring vaccination campaign to work, every person who has come into

physical contact with a suspected case must be identified, vaccinated, and then

monitored for symptoms.

While WHO experts say ring vaccination and contact-tracing are key to stemming

outbreaks, they are time-consuming, invasive, and hard to do effectively in rural

areas with patchy phone networks like Bikoro and Iboko, where the outbreak is thought

to have originated. A journey of just 20 kilometres in this region can take several

hours, and the vaccine needs to be kept at an extremely low temperature.

But containing the outbreak also depends on the willingness of the local community to

help – by raising the alarm when a case is suspected and by informing health workers

promptly and accurately of everyone an infected person has been in contact with.

Winning over the sceptics

While most people are cooperating and health workers say all the immediate contacts

of known cases in Mbandaka have now been vaccinated, rumours and conspiracy theories

have also taken root.

Hordes of health officials (WHO alone has sent 170 experts), aid workers, and

journalists have descended on Mbandaka, often making disconcerting demands or asking

difficult questions. Some locals are benefiting from an economic boom, but others

have been hit by unexpected price hikes and many are wary of the foreign invasion.

“The so-called Ebola is nothing but a curse. Ebola is a white man’s invention to

attempt to control Africa’s resources,” pastor Jean-Pierre Elumba told his riveted

congregation, meeting near one of Mbandaka’s many river ports. “Brothers and sisters,

whether this Ebola thing exists here in Equateur or not, the truth is that the

solution of Ebola lies in repentance, not in washing hands..."

Elumba’s sermon is the exception rather than the rule. Raphael Mbuyi, provincial

coordinator in Equateur for UK-based charity Oxfam, reckons four in five pastors are

on-side with the response effort. “It is the remaining 20 percent still resisting

that pose a problem,” he said. “And, among them, there are at least 80 percent that

say Ebola is a curse from God.”

Oxfam, which is taking part in a larger awareness-raising campaign involving the

Congolese government, UNICEF, and other international NGO partners, has recruited 120

local people to go door-to-door to get the facts out to as many families as possible.

“We are well aware of the rumours going around about the disease,” Mbuyi said.

“That’s why we are moving quickly to get the message across.”

In addition to buying radio air time to offer health professionals an opportunity to

discuss Ebola, Oxfam is promoting phone-in programmes that allow listeners to ask

questions about the disease.

Vaccine fears and changing customs

The traditional practice of touching and handling the bodies of the dead was a major

factor in the fast spread of Ebola in the 2013-16 West Africa outbreak.

One of the pillars of containing Ebola now is what the WHO calls “safe and dignified

burials”, whereby professionals handle the corpses and follow a 12-stage guide,

observing, as much as possible, local custom.

But not everyone is happy with the way this is going down in Equateur.

“I was in Bikoro and I was angry the way people were holding Ebola funerals,” said

Elizabeth Mokia, a woman in her 70s.

...

Bomboka said that before Médecins Sans Frontières opened a separate Ebola clinic at

Iyonda, 15 kilometres from Mbandaka, fear of the virus had been scaring people away

from the hospital. (There is now a second MSF isolation unit in Bikoro, and the

international medical NGO is setting up other treatment centres in Iboko and Itipo.)

“We ran out of patients,” Bomboka said. “And the maternity consultations became free

of charge, perhaps to attract patients and pregnant women to come. It shows you that

people want nothing to do with this so-called Ebola.”

WHO spokesman Tarik Jašarevic acknowledged possible side-effects from the vaccine but

said these were “typically mild”, including “headache, fatigue, muscle pain, and mild

fever”.

He also sought to reassure people, saying the vaccinations are free and voluntary (on

the basis of written informed consent only), and are approved by the Congolese

government’s ethics committee. Every person vaccinated receives two check-up visits,

three and 14 days after vaccination, Jašarevic added.

Making (some) progress

...

For the moment, at least, the Equateur outbreak appears to have been stopped in its

tracks. Oxfam’s Mbuyi, for one, attributes this to both the vaccine and the

awareness-raising campaign.

“We have seen an amazing change of behaviour in many people,” he said. “As a result

of what we have been doing, many people are going to hospital to be vaccinated, and

the culture of hand-washing is also being fostered in many areas and in households.”

Yet the vaccine hasn’t stopped some in Mbandaka from turning to alternative methods

to ward off the virus, and others from purveying their “cures”.

Francine Kibala, 49, claimed to have developed her own powerful “vaccine” from plants

in the giant Mai-Ndombe forest that are famed in Congo for their supposedly magical

powers.

“This solution, which was mixed with the mysterious water of Lake Mai-Ndombe, is

better and stronger than the vaccine brought here by the white people,” she said,

brandishing a darkish liquid she referred to as her “trophy”.

...

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication providing reposted

commentary and analysis on African issues, with a particular focus on U.S. and

international policies. AfricaFocus Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please write to this

address to suggest material for inclusion. For more information about reposted

material, please contact directly the original source mentioned. For a full archive

and other resources, see http://www.africafocus.org

|