|

Algeria

Angola

Benin

Botswana

Burkina Faso

Burundi

Cameroon

Cape Verde

Central Afr. Rep.

Chad

Comoros

Congo (Brazzaville)

Congo (Kinshasa)

Côte d'Ivoire

Djibouti

Egypt

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Ethiopia

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Kenya

Lesotho

Liberia

Libya

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Mauritania

Mauritius

Morocco

Mozambique

Namibia

Niger

Nigeria

Rwanda

São Tomé

Senegal

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Somalia

South Africa

South Sudan

Sudan

Swaziland

Tanzania

Togo

Tunisia

Uganda

Western Sahara

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

USA/Global: Contesting Health and Workers' Rights

AfricaFocus Bulletin

May 12, 2020 (2020-05-12)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

The global Covid-19 pandemic has made clear that the right to

health is not just an aspirational value. Suddenly, it’s a matter

of desperate self-interest for everyone, except, perhaps, those

insulated by enormous wealth. The same is true for the rights of

workers in the United States and worldwide: their work and their

consumer power are indispensable to a global economy facing

recession. The current crisis thus presents an opportunity to

expand the recognition and exercise of these pivotal rights,

accelerating efforts that were already underway before the virus

hit. But all too predictably, these efforts are running up against

stubborn resistance from forces that benefit (or think they

benefit) from the status quo.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains the latest essay in the series “Beyond Eurocentrism and U.S. Exceptionalism: Starting Points for a Paradigm Shift from Foreign Policy to Global Policy,” by William Minter and Imani Countess. The first three essays, in January and February, were followed in March by a special shorter essay “Can Coronavirus be a Catalyst for Thinking Globally?.”

The latest essay takes up the theme of economic rights,

particularly the right to health and workers' rights. The urgency

of these rights, both within countries and globally, is being

underlined with a vengeance by the pandemic. But while self-

interest as well as moral values demand universal application of

rights, the legacy of profound inequalities mean that the immediate

consequences are to ratchet up the differential application of

rights.

Today, May 12, is International Nurses Day, and the global Public Services International, which includes 700 trade unions representing 30 million workers in 154 countries, has issued a manifesto calling for universal public health for all.

Under the existing order, some lives matter more than others. And

those holding the greatest power in many countries and global

institutions are willing to sacrifice millions of lives around the

world, including many of their own political supporters, to

preserve their privilege.

For a related commentary on this point, particularly in the context of the United States, see “The Race-Class Narrative and Eroding the Racist Right” by William Minter and Prexy Nesbitt, reviewing two new books relevant to the potential for change, Merge Left and Dying of Whiteness.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Making Rights Universal: The Contested Cases of Health and Workers' Rights

by William Minter and Imani Countess*

* William Minter is the editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin. Imani Countess is an Open Society Fellow focusing on economic inequality. This essay is part of a multipart series beginning in January 2020. Thanks to Catherine Sunshine for editing the essays in this series.

The global Covid-19 pandemic has made clear that the right to

health is not just an aspirational value. Suddenly, it’s a matter

of desperate self-interest for everyone, except, perhaps, those

insulated by enormous wealth. The same is true for the rights of

workers in the United States and worldwide: their work and their

consumer power are indispensable to a global economy facing

recession. The current crisis thus presents an opportunity to

expand the recognition and exercise of these pivotal rights,

accelerating efforts that were already underway before the virus

hit. But all too predictably, these efforts are running up against

stubborn resistance from forces that benefit (or think they

benefit) from the status quo.

In the 20th century, World Wars I and II spurred the formation of global organizations whose mandates included expanding “universal” social justice and human rights. Yet implementation lagged far behind formal commitments, and even those commitments limited both the rights that were included and the people to whom they were presumed to apply. Thus the International Labour Organization, founded in 1919, opened its constitution with the claim that “universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice.” But the covenant of the League of Nations, founded the next year, failed to include the right of self-determination for all nations. Only two African countries, Liberia and Ethiopia, were members of the League. And campaigners for the rights of women, Blacks, and indigenous and colonial peoples found little sympathy among the architects of these new global organizations.

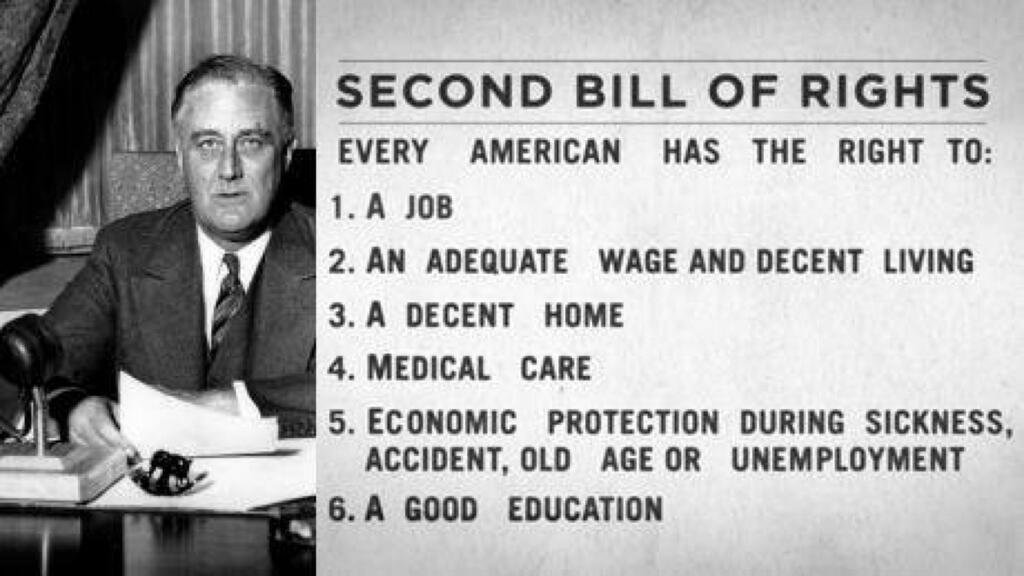

The interwar period saw the growth of right-wing authoritarian movements and states, and eventually the return to war. But at the same time, anti-colonial, civil rights, and labor movements around the world gained new momentum after World War I. Among the protagonists were war veterans of color who had been mobilized to fight overseas even though they lacked political rights at home. President Franklin Roosevelt also took steps toward expanding rights, although his New Deal was marred by the restriction of many of its programs to white men. An executive order in 1941 barred discrimination in the defense industry. And in his 1944 State of the Union message, President Roosevelt laid out a “second bill of rights” to apply to “all, regardless of station, race, or creed.”

After World War II, the United Nations and the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights embodied a similarly expansive view of

human rights. But the commitment to these principles by member

countries, including the United States, was hedged by many

limitations.

A “Liberal International Order”

Fresh from the Allied victory over Nazism in World War II, the

United States was a moving force in creation of the United Nations

in 1945. The UN’s initial membership of 51 nations included

Ethiopia and Liberia in Africa, China, India, and the Philippines

in Asia, and almost all the Latin American countries. Ironically,

white-ruled South Africa was also a member, and its leader, Jan

Smuts, played a prominent role as statesman, even though the state

he led was based on white supremacy. Indeed, white supremacy at

home and abroad continued to be the de facto norm for the United

States and other Western powers.

The “liberal international order,” according to Brookings Institution scholar Thomas Wright, is “generally defined as the alliances, institutions, and rules the United States created and upheld after World War II.” Its pillars are the security order centered in NATO and the UN Security Council, and the economic order defined by the Bretton Woods institutions (the World Bank and International Monetary Fund). In all of these, the United States and its Western allies have played and still play dominant roles. Whether this order can be preserved or adapted, in the face of the Trumpian onslaught, is a point of current debate among the U.S. foreign policy establishment.1

Human rights is generally included as only a minor theme in establishment discussion of this postwar order. Nonetheless, international human rights law and associated United Nations institutions have outlined a global agenda encompassing social, cultural, and economic rights as well as civil and political rights. This agenda is buttressed by a host of international agreements on women´s rights, workers´ rights, and more.2 It forms a framework for global consensus and an inspiration for civil society activists around the world. Yet in most aspects of this movement, the United States is at best a reluctant participant.

This was not always so. The negotiations toward the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 were led by Eleanor Roosevelt. Much of the language echoed lofty ideals from the Atlantic Charter and the “Four Freedoms” speech of President Roosevelt, both in 1941, which had inspired people around the world during World War II.3

Subsequent decades featured more hypocrisy than dedication to human rights ideals, both globally and in the United States. At the same time, the rapidly expanding membership of the United Nations provided a sympathetic forum for advocacy of universal ideals. The U.S. civil rights struggle and global anti-colonial struggles both reinforced and paralleled each other in demanding that the freedoms fought for during World War II should apply to all human beings without exception.

Yet it took decades of struggle before the landmark expansion of

political rights in the 1960s was achieved in the United States and

Africa. White-minority resistance remained a powerful force,

delaying the fall of white-minority regimes in Southern Africa to

the last decade of the 20th century. In the United States,

determined campaigns of voter suppression never stopped, despite

the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Subsequent decades saw the Republican Party's transformation into a

white-minority bastion. The most extreme opponents of human rights

for all, though they are a minority even among white Americans, now

have a firm grip on political power in the Trump era.

A spectrum of rights affirmed in principle

The rights in the Universal Declaration were enumerated in 30

articles with a wide scope, including political, social, cultural,

and economic rights. Although the generality of the language allows

for diverse interpretations, subsequent international conventions

have fleshed out the details of international human rights norms.

Specialized international agencies offer guidance and coordination,

although implementation is up to the signatory states.

The right to health, for example, is spelled out in many international agreements, including those mandating the responsibilities of the World Health Organization (WHO). The International Labour Organization (ILO), made up of representatives of governments, businesses, and trade unions, provides guidance on workers' rights, based on eight fundamental conventions and a host of other conventions and recommendations. The United States has only ratified two of the eight fundamental conventions and 12 of the other 182 conventions. Although ILO conventions are separate from the UN human rights framework, a 2016 UN Special Rapporteur's report spelled out how workers' rights are also inescapably human rights.

As documented by recent historians,4 human rights activists as well as states have been selective in choosing which rights to prioritize and what standards to use to judge compliance by states. In part, this is normal human hypocrisy, visible in the foreign policies of all countries. It is far easier to stress the faults of others than to apply the same standards to oneself. During the Cold War, the United States and its allies emphasized the lack of political rights in the Soviet bloc, while the Soviet Union and its allies pointed to the United States’ denial of civil rights to African Americans. For the U.S. government, tolerance of gross rights abuses in allied states of strategic importance has been standard practice since World War II.

What kind of rights?

Yet there are also substantive ideological disagreements in rankings of different human rights, by human rights activists as well as by governments, and these are apparent in the different levels of support for the international treaties that have been added to human rights law over time. A key distinction is between civil/political and economic rights. The United States is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of 1966, along with 172 other countries. However, it has signed but never ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which has 170 countries as full parties to the treaty. It has also not ratified the majority of additional international human rights treaties adopted by the international community.

Thus, while according a modicum of formal recognition to civil and

political rights, the United States has been an outlier in failing

to support economic, social, and cultural rights, and specifically

workers' rights, even in theory. In contrast to civil and political

rights, where the main need is to protect against abuses by the

state, the second set of rights requires proactive state

responsibility for their fulfillment. Strikingly, the most

prominent international human rights organizations, such as Amnesty

International and Human Rights Watch, have also generally limited

their portfolios to civil and political rights.

In recent decades, the principal challenge to a broad concept of human rights has come from the right, as a well-orchestrated intellectual and political campaign has elevated the rights of property ownership above all other rights.5 Instead of expanding the U.S. debate on human rights to meet international standards, the trend has been to roll back the limited achievements of the 20th century that expanded, however tentatively, the state´s responsibility to protect citizens’ rights. This retrogressive campaign has reached new heights under Trump, and resistance has had limited success. Yet this may be changing, for structural and demographic reasons and, most recently, because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

New focus on health and workers’ rights

The shifting landscape is most visible in revived demands for the right to health and for workers´ rights. Both fall under the category of social and economic rights, and both offer the potential to link domestic struggles for human rights to a global agenda. The potential for shaping public opinion is well illustrated by the role of National Nurses United (NNU), one of the most politically engaged unions in the United States today.

With some 150,000 members, NNU represents only a small fraction of the 12.5 million workers in AFL-CIO–affiliated unions. But nurses consistently rank first among professionals in respect from the public. The NNU has strategically maximized its impact, not only by actively organizing in the workplace, but also by targeting key public policy issues. Working with the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign, it has spearheaded the campaign for Medicare for All. And it has successfully campaigned for state-level standards for safe staffing ratios of nurses to patients. The NNU has played a key role in changing the public debate on the right to health to make this a fundamental commitment for Democratic politicians.

Accepting health and workers´ rights in principle, including the

assumption that government action is necessary to implement these

rights, is the foundation for applying these rights globally. Civil

and political rights often receive attention in foreign policy

because extreme cases of abuse are highly visible, particularly

when spotlighted by media coverage and by local and international

activists working in tandem to raise the issue.

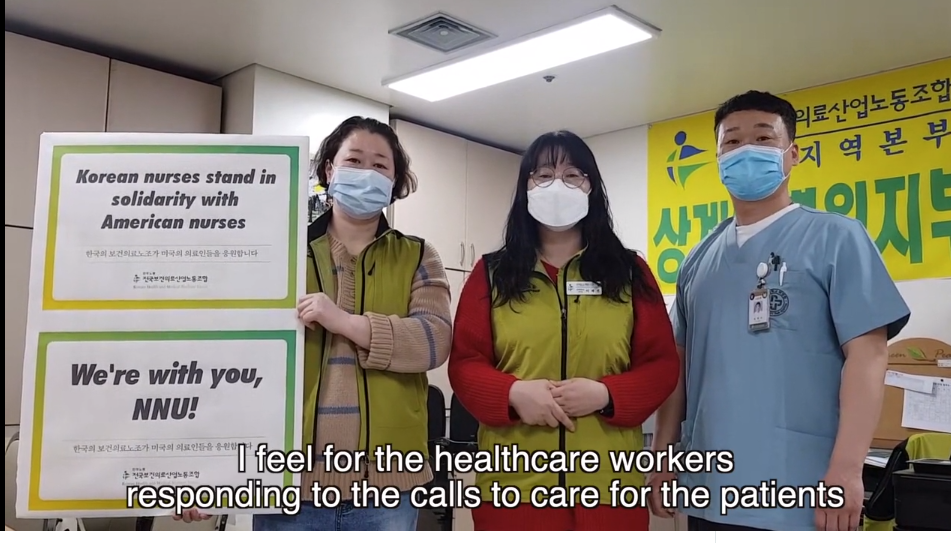

In some cases, workers laboring in the same industry on different continents have been able to build solidarity and confront multinational corporations. But the majority of workers worldwide are now service workers, many in the health and education sectors, or ´precarious workers´ in the informal sector. Government action, both national and international, is fundamental to any effective action to ensure their rights. Global union networks, such as Global Nurses United as well as Public Services International, which includes 700 trade unions representing 30 million workers in 154 countries, provide a framework for campaigning for the implementation of global standards. Such campaigns can stress the dual objective of serving public needs and ensuring the welfare of public service workers.

U.S. campaigns for implementation of human rights at home should begin to break from U.S. exceptionalism and draw inspiration from global standards developed through international collaboration. While implementation of rights always depends on mobilization to influence national governments, participation in the international dialogue provides access to new thinking about changes that are taking place at a global level. Thus, the recent Global Commission on the Future of Work lays out a “human-centred agenda for the future of work” to meet the challenges of globalization, automation, and rise of precarious labor. The goal of decent and sustainable work for all requires both public investment in people´s capabilities and changes in the institutions that manage work, in both rich and poor countries.

The first prerequisite for government action, in turn, is a strong union movement. And despite the low rate of unionization in the United States, compared to most other developed countries, there are some encouraging signs of revival. In 2019 a Gallup Poll showed the percentage of Americans approving of unions rising to 64%, the highest rate in 50 years. Although union strength is still at a low ebb, new energy is visible in the autoworkers´ strike, campaigns such as the Fight for $15 minimum-wage campaign, and the wave of teacher strikes in both blue and red states. Within the Democratic Party, notably, political support for unions has been reviving, with increased attention from presidential candidates. And there is recognition that changing the legal framework to support workers´ rights is a high priority.

A key factor behind these changing attitudes is the demographic and occupational transformation of the working class. While the white male manufacturing worker remains the iconic image favored by pollsters and the media, it is nurses, teachers, and other service workers who are becoming the visible face of working-class activism. And that face is diverse. Some blue-collar occupations are now predominantly female,6 and almost all include large numbers of people of color and immigrants. The three largest unions in the country are all composed of service workers, and the trend toward more service jobs is sure to continue. Moreover, to the extent that programs such as the Green New Deal and Medicare for All advance domestically, there will be a further boost in service jobs, including those in public service, from local governments to federal agencies.

This changing workforce can potentially provide a growing constituency for global perspectives. The trade union movement faces many internal issues, including with hierarchy, patriarchy, and racism. But progressive unions such as the NNU, the Chicago Teachers Union, and others, as well as parallel campaigns such as Fight for $15 and Jobs with Justice, are having a grassroots impact. Many of their leaders and members are also open to a transnational perspective, influenced by shared objectives with workers in other countries and by the increasing numbers of recent immigrants in their ranks.

April 20 - Nurses in South Korea, one of the countries with the most successful response to Covid-19, send a video message of solidarity to the National Nurses Union.

What difference does a pandemic make?

Even as these changes reshape the U.S. workforce and labor movement, the Covid-19 pandemic has shined a harsh light on U.S. denial of the right to health and workers´ rights—and the impacts of this denial on the whole society.

At this writing in May 2020, the need for massive government action to address the pandemic is widely recognized, except by those at the top levels of the Trump administration. The crisis has shocked many Americans into a new awareness of the inequalities of race, class, occupation, and place, factors that to a large extent determine who bears the greatest burden and greatest risk. Front-line medical workers and essential workers in meatpacking plants and in agriculture, for example, are disproportionately people of color, many of them from immigrant communities.

Around the world, many nations and multilateral institutions are mobilizing to respond to the virus. Promising experiences can be found in countries such as South Korea, New Zealand, and others, and in breakthroughs such as the rapid testing kits developed in Senegal. Africa overall, despite many vulnerabilities, has had excellent leadership from multilateral institutions such as WHO and Africa CDC, as well as from some governments such as South Africa and Senegal. African countries have so far managed to stay ahead of the virus curve, although the continent, like other developing regions, is hit hard by the economic impact of national shutdowns, as well as by fallout from the global recession.

Yet the Trump administration, instead of learning from other countries and advancing plans for controlling the virus and expanding stimulus and recovery measures, is ramping up denial. It is shifting responsibility to the states while denying them needed resources. It casts blame on China and on the World Health Organization, seizing the opportunity to further weaken global institutions. Fortunately, other nations are stepping up to support WHO, and the organization’s Covid-19 Solidarity Response Fund has raised over $200 million from almost 300,000 donors.

While some U.S. states, particularly the early responders on the West Coast, may have flattened the curve, most have not. And by prematurely reopening their economies, some are courting renewed exponential growth of the virus, egged on by President Trump and by protesters mobilized by far-right networks. While no one can accurately project the future, most experts expect that the national toll of the pandemic will remain at the current level or even continue escalation into next year.

Democratic members of Congress can propose actions, such as additional stimulus bills to aid states and local governments and even more ambitious plans such as an essential workers’ bill of rights. But further action also depends on concessions by the Republican-controlled Senate and the administration. And even implementation of measures passed is limited by incompetence and by ideology and built-in bias.

It is clear that neither confronting the virus nor absorbing the lessons it can teach can rely on the White House. Instead, leadership is falling to state, city, and local governments, along with an outpouring of mutual aid efforts. These responses, shaped by politics, are highly uneven, with Republican-controlled states less likely to take strong action. But as the virus spreads in red and rural states over the coming months, mounting deaths in these areas may eventually convince some skeptics that government has a role to play.

The toll of Covid-19 deaths is revealing in real time the deadly effect of right-wing Republican policies. As the impact continues to mount in red states as well as blue, the impact will still be unequal by race and class. But whites who have supported the right-wing agenda will not be spared by the virus.

The contrast between governors and mayors who act to protect their population and those who do not will be inescapable. Despite efforts to divert the blame to foreigners and minorities, the virus will continue to expose the failures of the anti-government message and enhance the case for inclusive government responsibility.7

Changing minds to accept the right to health and workers´ rights as fundamental principles, and even more changing government policies, still face enormous obstacles. But accepting these rights at home, in the context of a global pandemic, should be and hopefully can be, a first step toward accepting its application to the entire human community living on one planet.

Note: Links to books in this essay are to the new nonprofit http://bookshop.org, which provides support to local independent bookstores, as well as providing an affiliate option for others who want to promote books without reinforcing Amazon’s monopoly power. Disclosure: AfricaFocus Bulletin is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a small commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Notes

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources,

see http://www.africafocus.org

|